Part Three: 1961 to 1980

A new name, a new building, and an outdated idea: Which did not end up belonging?

As the 1960s began, an important name change would take place at Taylor Township’s original (and largest) shopping mall. With the change from the non-discrepant “Green Center” moniker it had since opening in 1957, the new name, Taylortown, would show township pride more effectively. The mall itself was a financial boom, and would hold onto its title as the township’s largest for several more years.

Having long outgrown their original location at Biddle & Chestnut streets in Wyandotte, a much larger, sleeker facility for the YMCA / YWCA opened to the public on September 28, 1960. It was located on Fort Street just north of Eureka Road. The original Wyandotte site would later be replaced by one of the first riverfront high-rises: the Wyandotte River Tower.

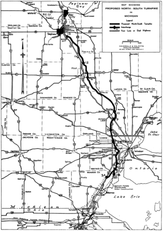

Proposed routing of the Michigan Turnpike, c.1955 Proposed routing of the Michigan Turnpike, c.1955 | Back in the news – one more time – was the belabored Michigan Turnpike Authority, whose plans for toll expressways were on hold (and seemingly defeated) since 1955. Giving their viewpoint one more attempt, they attempted to undermine any progress on the Seaway Freeway project by putting forth one more proposal in 1961: to pay for expressway construction through the sale of bonds. This idea would fade quickly, as any potential financiers of construction projects would only build on the assumption there would be no competition from any other entity, be it business or government-based.As the Seaway Freeway route was being finalized south of Downriver, it was suggested that the portion of proposed freeway from Detroit to Toledo be electrified, courtesy of General Motors. Initial electric testing had been conducted at Ohio State University, but the results were apparently never made public, and the entire route of proposed freeway would be built out of traditional means.The State Supreme Court decided they had waited on a final death blow to the MTA long enough: in 1962, the MTA was officially repealed by law, leaving the U.S. Interstate system and the state’s plans for freeways such as the Seaway project intact. No appeal action was taken on this decision. |

Up to 1964, the Downriver area hosted three oil refineries within its boundaries (as opposed to one refinery in the state of Michigan today). The smallest of these closed in 1964, a little-known facility named Petroleum Specialties Incorporated (PSI). Located on Peters Road near the southern border of Brownstown, PSI may have felt the competition for resources being waged with Socony-Vacumn’s refinery in Brownstown. Rather than close all operations down, they would settle in as an oil storage and distribution facility rather than a refiner. It would only be a matter of time, however, before serious, potentially fatal flaws, would make themselves known to an unsuspecting public.

The Blue Oval picks the Village of Woodhaven for a major development

Ford Motor Company ended up choosing the village of Woodhaven as the site for its fourth stamping plant construction project since World War II. Within a month, groundbreaking took place and the 400-plus acre plot, the former Trombley soybean farm, began to take shape. The Trombley family (Alice, and brothers William & Lawrence) had sold their land to Ford a couple years prior.

| “Operating our plant in a community of about one thousand people is bound to cause some dislocations in its way of life. We recognize that. But Woodhaven has already anticipated change by moving from the village to the Mayor/Council form of government.” – HENRY FORD II President : Ford Motor Company | In an astonishingly short amount of time for a 400-acre project, the new Woodhaven Stamping Plant started partial activation in January of 1965. The first press, weighing 272 tons, was unveiled and activated on April 7. The first approved stamp for shipment, a 1965 Mustang quarterpanel, was produced on June 17, 1965. Fully staffed with an initial workforce of 1,880 under plant manager Willis G. Hummel, Ford Chairman Henry Ford II would address a crowd at the plant’s dedication April 15, 1966. But not before issues & votes threatened to a geographer’s dream upside down – again. |  Woodhaven Stamping Plant employee entrance, c.1965 Woodhaven Stamping Plant employee entrance, c.1965 |

Wyandotte’s Bacon “Library Says ‘Shhh!’ – and means it”

The up-and-coming generation of teenagers in the 1960s were more rebellious in nature, owing much to the strife occurring in the country as well as the increasing situation in Vietnam. Combined with funding problems, it would put Bacon Memorial Public Library in the national crosshairs early in 1965.

The funding issues resulted in the library being open just three days a week and, when the facility was open, up to 120 teenagers were known to congregate outside and inside at one time, since there was little of recreational value for them, and they had no other place to visit. They would crowd the entrance, according to Library director Louise Naughton, to the point patrons could not get into the front door.

Up until this point, the Wyandotte Police had been called to quell any unrest or suspicious activity. But by January 1965, a private officer from a Detroit Police agency ended up taking over during the evening. Mrs. Naughton believed it was for the best, even though the initial thought of an arrangement was a little disheartening. It may have simply ended there if the Detroit Free Press had not seized on the story and headlined it with the wording shown above.

It the article, which was likely overkill on the situation, a photo of the evening shift officer was shown, as well as an editorial cartoon showing a caricature of authority springing from a library shelving unit, shoving the teenagers aside as the library director looked on, horrified. Their coverage would end up being picked up by the Associated Press, making headlines in newspapers from Kalamazoo to McKeesport, Pennsylvania (“Teenage Romance Ends At Library,” “Private Police Hired To Stop Necking”), and even earning “Page 2” space on Paul Harvey’s nationally syndicated radio show.

Fortunately, Downriver, Detroit and Michigan were spared the country’s worst electrical disaster in history. On November 9, 1965, the Great Northeastern Blackout would affect most people living in the New England states, with the problem traced to a safety device at one of the hydro-electric stations on the Niagara River in Ontario. Despite the outage affecting much of southern Ontario, Michigan was not affected as they did not tie directly into the Niagara power grid at the time.

The Mid-1960s: A time of attempted territory annexations

| As Ford Motor Company gained the site for its West Road Stamping Plant and began clearing the former Trombley farm, Woodhaven would become a city in 1965. This meant that Brownstown Township lost two major tax providers: Socony-Mobil’s oil refinery, as well as tax potential from the new Woodhaven Stamping Plant. Brownstown government would seek a four-mill addition to their tax rolls, but would have to fight off annexation again.Successful annexation of land had not occurred since August of 1955, when a 30-foot section of Fort Street land was taken by Wyandotte in a largely procedural move with logical reasoning. Yet, a vote was set on January 8, 1966, in the cities of Rockwood and Southgate, plus Brownstown. Rockwood, which only became a city the prior year, was looking to annex a portion of the village of East Rockwood. Southgate was looking to make its first expansion since it incorporated seven years prior; the new city boundaries would have gone as far south as King Road, and as far west as Telegraph… more than doubling its size. Southgate mayor Robert C. Reaume spent much time talking to citizens living in the affected areas, promoting Southgate’s full-time Fire and Police Departments as advantages, in addition to a fully-functional Public Works Department. |  A neighborhood in Rockwood around the time of their annexation request, c.early 1960s A neighborhood in Rockwood around the time of their annexation request, c.early 1960s |

Naturally, Southgate mayor Reaume and Rockwood mayor Irving Brewer were for the project, Brownstown Supervisor Donald Mahoney was hearing none of it. Brownstown ended up with its own plans, applying to become two cities of its own. Seeking to grab the East Rockwood village as its own, that portion would become the city of Brownstown East. A northeast section of the township would then be incorporated as the city of Brownstown.

The radical realignment of lands would only take place if Rockwood & Southgate approved their referendums, and if the separate issue Brownstown had on their ballot (to simply maintain its current township borders) failed.

Needless to say, the borders would stay where they were. Potential Southgate residents defeated the deal 210-45; actual city vote was 2071-166 in favor. Brownstown turned down the moves by Southgate, 705-84. In Rockwood, city voters approved annexation of East Rockwood, 303-35, but the small village held on and put the referendum to rest, 254-104. Combined voter turnout was almost 45%. Southgate mayor Reaume expressed his disappointment at the annexation loss, but commended the residents of Brownstown for their voter participation, even if not the desired result.

Accident at original Fermi plant puts entire area – eventually – on notice

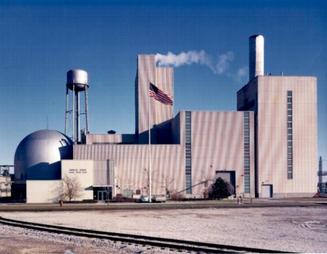

The original Fermi complex today.

A near-meltdown of the original Enrico Fermi Nuclear Power Plant near Monroe (known today as the former Fermi I) occurred on October 5, 1966. Melted fuel in the reaction chamber was the cause, although it had not leaked out for there to be an actual disaster declared. But with nuclear power still relatively in the learning stages, workers at Fermi did not know exactly how to treat the condition, and no prior experiences were on record to tell how dangerous the situation could become.

To the credit of the workers at Fermi, they managed to quickly think of a containment plan, but executed it very carefully, checking and double-checking at every step of the matter. Experts from England, France, Scotland and the United States met to discuss a solution, which was to extract the melted fuel from the reactor. The process was likened to taking a person’s appendix out through their nose nostrils, but it was eventually done successfully.

It was decided that an overall plan had to be implemented to warn residents of impending disaster, and necessary evacuation procedures. A book released eight years later would find that a similar accident of full-force could kill 3,400 people within a 15-mile radius, with 43,000 being fatally affected in the second ring (up to 44 miles away), with an estimated property damage amount of seven billion dollars. Fermi I was retired from service not long after an additional leak was detected at the facility in May, 1970.

Detroit Riots of 1967 take a toll on people’s travel and safety concerns

For the first time since he assumed ownership of Bob-Lo’s amusement park in 1949, Todd H. Browning was forced to shut down the attraction in peak season following the 12th Street Riots of July, 1967.

Fearing looting and other damage to the iconic Bob-Lo boats, the Columbia and Ste. Claire were driven from the Detroit dock to Bob-Lo, where they would remain tied up for eight days until the ordeal in Detroit passed.

More concerns about general safety began to be brought up by potential visitors, who began avoiding downtown Detroit in greater numbers and, hence, the Detroit Bob-Lo dock. The other docks in Amherstburg, Gibraltar and Wyandotte continued to do well, but attendance still suffered as a result.

Downriver communities unite to assist Detroit in its darkest hour

Meanwhile, the riot itself would grab headlines around the nation and world. Its root cause – the raiding of a Blind Pig on 12th & Clairmount – hearkened back to Downriver’s darker chapter of the 1920s, although the vandalism, looting and overall crime rate in 1967 was much higher.

On Monday of that week, Downriver mayors, police and fire chiefs met with Wayne County Sheriff Peter Buback; from which each mayor put forth his “State of Public Crisis Emergency” message. An overall curfew would be imposed at 9:00 PM daily until further notice, and it fell under the strictest enforcement in local history. Fines for infractions were expensive for the time; a typical curfew violation could cost up to $110. Liquor of all types was banned from sale for the duration of the proceedings, as were gasoline containers. Guns and ammunition were also barred from sales and holdings, except to police and other licensed law enforcement.

All police personnel were called in to work, some for up to 24 hours straight on the first day. Each department’s force had the ability to become a tactical unit in case violence spread south of Detroit. Fire Department equipment from Gibraltar and Wyandotte were shuttled to Detroit to help battle the increasing arsons at 12:00 noon on Sunday. Trenton’s forces were on standby alert to tend to any incidents happening Downriver.

Most importantly, a blockade was put into place by the Gibraltar, Trenton and Woodhaven Police Departments, protecting the southernmost cities and townships in Wayne County. This proved to be a wise call, as word had come in that additional youths from the Toledo area were planning to transport north to Detroit to aid in the increased crime. It was feared that such groups might utilize Elizabeth Park as a marshalling point. Such groups did not make their presence known.

It may be noted here that Gibraltar and Grosse Ile possess the ability to shield themselves completely from the mainland. By simply turning the Free Bridge and Toll Bridge halfway around, and by setting up a blockade to prevent access to North, Middle and South Gibraltar Roads, those municipalities were more or less guaranteed maximum protection.

Overall, incidents Downriver were few and far between. A heavier police presence was required at Korvette’s in Southgate after a threat was phoned in to the department store on Monday. That night would bring a mild spate of looting and rock-throwing in River Rouge, but that would be quelled by the following morning.

Many witnesses – and local politicians – would say they were impressed by the can-do spirit, as well as the amount and quality of help provided by emergency personnel and everyday citizens during this time. Groups got together to donate necessary food, clothing and other supplies for Detroiters displaced by the arsons and crime. Wyandotte would be the first Downriver community to lift its curfew on Thursday, as they were the only city to have the power to decide that on its own. By the following week, routines Downriver would return to normal.

Perhaps owing to the great response among Downriver communities during the Detroit Riots of the prior year, fifteen mayors would meet in Trenton as part of a Mutual Aid Committee to develop an overall area disaster plan in March, 1968. The bonding of so many local politicans was unprecedented to the public at that time, as the city heads were part of the new Southern Wayne County Mayor’s Committee, formed in 1967.

At the same time, while personal bonds were growing, building was taking an unexpected halt in Southgate. Mayor Robert Reaume halted all housing construction in the area called Drain District #5, bordered by Northline, Mulberry, Superior and Allen Roads. The poor overall condition of the Woodruff Drain (which ran along Northline) led to the possibility of poor foundations in newly-constructed homes; of which previous efforts to relief the difficulty had gone unheeded, necessitating this temporary construction ban.

Taylor’s city formation gains two sweet deals

The original “main entrance” to Southland in 1970.

Following the 3/4ths majority vote from a couple years earlier, the final new city Downriver would make its mark by the debut of Taylor, under the leadership of Mayor Richard Trolley. One of his first major ceremonies as Mayor would be the July opening of Southland Mall.

Completing the “directional-land” malls, it was originally anchored by J.L. Hudson, Kroger and Woolworth & Woolco. It would be state-of-the-art for its time, with modern decor inside featuring four cascading waterfalls, a metal bar sculpture, a towering bird cage and a fish tank, both anchoring the corridor between the (then) east and west courts. The ribbon cutting in July would conclude the four year design and construction project and was very well received. The Hudson’s store in Lincoln Park would close and be quickly replaced by a Farmer Jack store, sealing off the basement and second floor areas, which have not been seen by the public since.

Replacing the old Tic-Toc hamburger stand on Telegraph south of Ecorse Road would be a future giant: Hungry Howie’s Pizza opened its debut location just south of its current building.

Hudson’s and Lincoln Park’s MC5 get into a record squabble

Southland’s initial reputation was solidified mere months after opening, as Downriver shopping habits were forever changed. It would be the actions of Downriver’s most famous rock group that would give Southland’s new anchor tenant – J.L. Hudson – some unwanted headaches.

The Motor City Five – best known as The MC5 – had formed in Lincoln Park in 1964 and within a few short years, their stature had grown exponentially, headlining concerts at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit. Their initial album release, Kick Out The Jams, was recorded entirely at that venue and would become Billboard Magazine’s ninth-best Live Rock album of all time.

As was often the case with the atmosphere in late-1960s music as well as the MC5’s raw roots, one song had a vulgar verse written for it. Hudson would take the group to task by refusing to carry the album in their stores. Since Hudson still had huge clout in the industry say-so, this affected sales and potential profit for the MC5.

Reacting passionately, the group took out a full-page ad in the offbeat Fifth Estate magazine, increasing the scope of vulgar scorn to the department store itself. The chain then took the liberal step of pulling the entire stock of its record label (Elektra) off the shelves. Again, owing to its continued industry-wide respect, the move by Hudson now became bad for Elektra’s bottom line, to the point the MC5 would eventually be dropped from the label altogether. Hudson would continue to back this ban throughout MC5’s later signing with Atlantic Records.

Though two more albums would be released under the MC5 name, the charm appeared over. Within a few years, they would officially disband their original lineup. But time would later show that Downriver’s appreciation of their home-grown talent would grow to epic proportions, spanning different generations of listeners.

The big news in 1970 would be in the aviation field. After 42 years of dedicated service as a naval air field, Grosse Ile would open to the public as a regional, township-owned airport, code named KONZ. It would handle the small prop aircraft that neither of the three major airports serviced.

I-75 would officially receive a name in 1970, as a ceremony on September 17 christened the Downriver section as the Fisher Freeway, named in honor of the Fisher brothers, who formed and ran the famed Fisher Body plants in Detroit.

Tall things were in the works as 1971 began, with construction well under way on the Security Bank skyscraper, located just north of the former Wonderland Park at Fort / Pennsylvania / Trenton Roads. When completed, the landmark structure would be billed as the tallest building between Detroit and Toledo, a rank it would hold for many years.

Trenton Theater ushers in an uncomfortable film industry locally

Trenton Theater in 1973.

In late 1972, the venerable Trenton Theater would change hands. New owner Lawrence Moore of Ferndale signed an operating license on December 18 to continue operations as they had been doing. A further agreement signed by Moore on January 10, 1973 assured that family-fare films would continue playing the bill. The first few weeks fell comfortably under this routine, but a sudden jolt would be felt around the community on January 29, 1973. This was when the marquee would now read, “Adults Only,” as it would become the first of the local moviehouses to show X-rated films.

The city’s response in protest was immediate. Officials felt betrayed, as they felt the 1972 agreement they signed with Moore would guarantee the X-rated fare would not air at the theater. The pact was made verbally as well as in writing, accompanied by a $10,000 bond, a gesture of goodwill, from Moore himself. Theater worker George Koates would vouch for the facility, claiming the movies shown were no different than from others showing in other metropolitan adult complexes. The movies, he argued, did not fall under the State and Federal definitions of “obscene,” and therefore did not violate the terms of the 1972 agreement with Trenton.

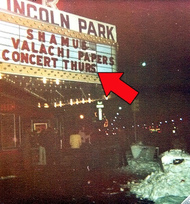

Park Theater in Lincoln Park, c.1972

Other locations with storied pasts, such as the Lancaster, Mel, Park, and even the venerable Wyandotte Theater would begin to cater to the more adult crowd with X-rated features headlining their bills, at a time when many houses in downtown Detroit were following suit in order to stay in business with the newer, more traditional complexes springing up in the suburbs. On the opposite end of the spectrum, drive-in theaters hit their peak at this time, with 132 operating state-wide.

Trenton’s quick actions would force the Trenton Theater to close barely a week after debuting adult fare, as their operating license was revoked due to “material misrepresentation of facts.” Bomb threats had also been phoned to the facility. Despite this, attorney Steve Taylor, representing owner Lawrence Moore, insisted the theater would continue to operate, especially since he and his client considered the revocation was handled illegally (for example, no notice of a hearing was given to discuss the procedure). In addition, Taylor stated that Moore “signed away his First Amendment rights,” by inking the 1972 deal with the city.

A trial involving projectionist Neal Brandt accused him of operating the theater without a valid city license. The case was heard by 33rd District Court Judge Gerald A. McNally; the resulting decision on February 14 was deflating for the city and its citizens. The theater would continue to operate as it had before. McNally agreed the revocation process was handled illegally: the city did not call a proper hearing, due process had not been followed, and all charges would be dropped. McNally would further state his decision had nothing to do with the level of obscenity shown in the films, cited Moore’s right to Freedom of Expression.

As McNally dropped the case, a counter-suit seeking injunction against city interference, being prepared by the theater owners against the city, was likewise dropped.

Downriver would show America how to bowl

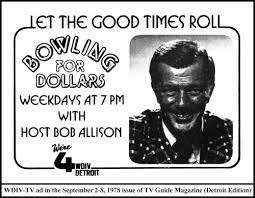

BOWLING FOR DOLLARS

Bowling, on the other hand, was much more family-friendly than the former cinema venues, and there was no one better able to prove that than the citizens of Metro Detroit. The area had been known as the unofficial “Bowling Capital Of The World” for decades, since the old brewery-sponsored teams made Detroit one of the hearts (along with Chicago) of bowling activity. More BPAA-registered bowlers came from the Detroit area than any other place in the world. Yet Detroit did not have a bowling show to call its own, other than perhaps the occasional event produced by the Professional Bowlers Association. This would change in a big way by 1973.

Many metropolitan areas across the nation were starting their own “Bowling For Dollars” shows, where temporary lanes would be constructed inside various television studios. The competition factor would be eliminated, as bowlers were bowling individually for prizes. The Detroit area attempted the telecasts, at first to no avail – or ratings.

| Channel 4’s next resort was to tap into a local radio show host’s talents, to see if he could keep the program from being canceled. Bob Allison, host of the “Ask Your Neighbor” radio show, was initially reluctant to make the venture into television; he was comfortable being a radio voice without a face. Once management piqued his interest (and he campaigned for listener approval on his radio show), he made the journey to Claster Productions (the producers of the popular Romper Room series), who were producing the individual telecasts: they crowned the Baltimore production as the best of its class.Allison was not impressed with Baltimore’s output, as he felt too much time was spent on introductions, and not enough of it on the bowling itself. He told Claster Productions to allow him to try a different production method, which he guaranteed would be the industry standard within a year of its re-release. Given the go-ahead, Allison went to Allen Park’s Thunderbowl Lanes, whose Arena section was built for productions of this stature. We’ll produce the show, Allison told the proprietor, and people will end up “know(ing) your place.”Being the first Bowling For Dollars series to eminate from an actual bowling center, with introductions shortened and the main focus turned to the actual bowling, Detroit’s Downriver version did become the standard to which all future productions would adhere to. Bowling For Dollars would become the highest-rated local television show ever produced, and landed Thunderbowl Lanes among the best-known and highest-ranked bowling centers in the country. |  From TV Guide Magazine, September 2, 1978 edition. From TV Guide Magazine, September 2, 1978 edition.  |

Grosse Ile’s fight against over-development and Urban Sprawl gets a huge boost

In early 1973, tentative plans had been made by Grosse Ile officials to consider a bid for an 878-unit apartment complex to occupy an 88-acre area near the Macomb Street business district. This would send alarm bells ringing among many island residents.

On April 8, more than sixty residents gathered at Grosse Ile Golf & Country Club to reactivate the Active Island Defenders (AID), a neighborhood watchdog which had begun fighting unnecessary development concerns in 1957. Driving their anger was the proposed number of 1,300 multiple housing units being erected over a two-year period east of Meridian Road, while a similiar project near Grosse Ile Municipal Airport would have developed 43 acres with 232 apartment units.

The following night (April 9), at the bi-monthly meeting of the Township Board, 103 residents would be in attendance to voice their disapproval of the main (Macomb Street) project submitted by Kaufman and Broad Homes of Southfield. Grosse Ile Supervisor DeWitt (Dewey) Henry stated the island community was at a “crossroads” regarding increased development. Nine houses were added in 1971, but the number would increase to 44 in 1972. This was much too fast for the community.

Instances such as these would figure in Grosse Ile’s future history, showing that decisions against unnecessary building, as well as care for natural areas, would help define their expanding leadership role in their conservation plans in today’s modern times.

Trenton Theater’s curtain goes down on a brief, forgettable era

Trenton Theater owner Lawrence Moore (far right), and projectionist Neal Brandt (at left) during the initial meeting protesting Trenton Theater operations. They would win that battle, but only temporarily.

Shortly after 33rd District Judge Gerald McNally had ruled in favor of Trenton Theater owner Lawrence Moore and projectionist Neal Brandt for the right to show adult-oriented films, the city of Trenton passed a new ordinance governing provisions for defining pornography and obsecnity as it applied to the city. This was given a further boost by the Federal Government who, on June 22, 1973, issued an important proclamation giving individual cities the ability to decide for themselves what movies, books, or other media they (themselves) considered immoral. Their rulings, therefore, would rank over state statutes. At this time, Michigan still did not legally define what the terms meant, or to what degree.

On that same day, the theater would also close voluntarily, as it was implied the ownership wanted to “lay low” for awhile. Reopening in September 1973, they would be shut down again that same day. Owner Moore and new projectionist Charles Holt would be brought before Judge McNally, resulting in a $2,500 personal recognizance bond for each. There were talks at this juncture of Moore voluntarily surrendering his operation license.

The saga would finally end on September 21, 1973. Moore would act on his informal verbal promise and sign away his rights to the Trenton Theater, and promptly remove the “adults only” sign on the marquee. A September 25th court trial date to be overseen by Judge McNally would therefore be canceled. Trenton Mayor Isadore Mulias agreed with passing on the need for trial, stating it would save the city time and money, given the facility was already closed.

First reconstruction of I-75 draws a nine-month headache, an accident, and retribution by Rockwood

Barely eight years after Interstate 75 was constructed in the southern Downriver area, reconstruction to allow for widening of the freeway (from two lanes to three), as well as a new interchange for Huron River Drive was taking longer than anticipated.

A September meeting of the city council directed city attorney Richard Smiertka to mail letters to state officials letting them know of their concerns, which included excessive dust, noise, and re-routed automobiles. Fears centered around possible accidents involving bicyclists choosing to travel underneath the Huron River Drive viaduct instead of across it. In fact, a three-car collision on August 28 had killed two brothers from Huntington Woods. The letter-writing was suggested by D.C. Bowen, supervisor of the reconstruction project, claiming it would be the most effective way for the contractors to get the message.

Rockwood police chief Bernard Herzog weighed in, mentioning the 45 MPH construction zone mandate was rarely enforced, and the zone itself was not long enough to assure adequate safety. Further, the State Police had been reluctant to patrol the area for unspecified reasons. The project would also be threatened with another possible extensive delay, as news of a possible equipment operator strike was made known.

Final Downriver annexation attempt hand-delivered to Michigan’s Boundary Commission

To date, the last bid to annex nearby lands was made by the city of Gibraltar in September, 1973, as they desired to capture a portion of Brownstown Township; namely, the Fort Street / Vreeland Road area. This bid would be initially denied by the State Boundary Commission due to a technical error in the plat description, but mentioned they would accept a revised version of this proposal. City Attorney Michael Russell would be authorized by city council to “hand-carry, if necessary,” such a revised petition to Lansing.

“Captain Bob-Lo” passes away at age 90

Joe Short, circa early 1970s.

The Bob-Lo amusement park was saddened to hear of the death of Captain Bob-Lo, Joe Short, on Christmas Eve of 1974 at age 90.

Mr. Short had been recruited from Ringling Brothers Circus several years earlier by Bob-Lo to provide entertainment as the boats were being loaded. He would work whenever the mood struck him, and he was a true professional at his craft: absolutely no one dared tell him how to go about his work.

Children were the specialty of the 4′ 4″ entertainer, who would also play one of Santa’s elves at the old Kern’s Department store in Detroit.

When initially admitted as a patient, he received no visitors. Word quickly spread of this and hundreds of well-wishers would end up mobbing the hospital he was staying at. The Detroit Fire Department’s auxillary clown unit acted as his pallbearers at his funeral.

Riverview looks to repurpose its landfill and set a precedent

The north section of the Riverview Land Preserve today. It was in the spring of 1976 when the first concrete suggestions were made as to its repurpose. (Photo: Rebecca Cifaldi)

Headlines went out the first week of January 1976 incorporated an un-heard of suggestion. The Riverview Landfill, in operation since 1968, was due to have its credible life expire within six to eight years and be closed off. The city of Riverview was in close contact with landfill engineer John Jenkins, who represented Jones & Henry Engineering, Ltd. of Toledo. The proposed idea was for a ski hill, something not seen of that stature before Downriver.

At the time, the hill was almost 150 feet high, but could be extended to 165 feet, or even 175 feet if an additional ten feet cap of earth was laid. This would allow for three potential ski lanes with a 12% sloping grade. The project would start with beginners’ level slopes only, extending to intermediate and advanced skiing in later phases. The ski hill in its full form was expected to be open by the 1979 holiday season.

Additional announcements included making the entire area near the landfill user-friendly, as a 34 acre lake was proposed adjacent to the hill. The lake, which would be 30 feet deep in spots, would be fed by up to 175 million gallons of filtered water from the Frank & Poet Drain. The city could not rely on sanitary water (too expensive) and did not see themselves mining for mineral water underground. It was also mentioned that the lifespan of the hill could be extended indefinitely, as the Riverview School District proposed a land-swap deal which would give the Land Preserve additional acreage to the south and west to continue its operation into the 1990s.

“Controlled burn” demolishes old Naval Air Station Captain’s Quarters

The headlines of the March 4, 1976 News-Herald looked ominous: firefighters battling a real-life blaze in an old building with “arson” appearing in the first paragraph. But the fire was deliberately set by firefighters participating from five communities in addition to Grosse Ile. Downed as a result of this training exercise was the old Captain’s Quarters builiding at Grosse Ile Municipal Airport. This was one of the first major tests of the effectiveness of the future Downriver Mutual Aid system. A total of 110 personnel aided in the operation, which resulted in the abandoned building leveled in ninety minutes.

Grosse Ile Fire Chief Joe Miller said some initial problems did come into play, with the staged fire burning out of control in the middle of the building; but fires set on either end of the structure burned to satisfaction. “We learned a lot,” admitted the chief.

After years of haggling among local politicians, approval was finally granted for the Riverview Co-Operative Senior Citizen Apartment tower, to sit on Pennsylvania Road behind Korvette’s and next to St. Cyprian Church. This would be Downriver’s tallest structure to serve this purpose for many years.

Selection and quality of movies created their own disturbing plot Downriver

| “It is unfortunate and disheartening that recent court fights show that a community’s (X-rated) law does not stand up in court.” – WILLIAM SULLIVAN Wyandotte Mayor (1976) | A concerning streak, meanwhile, finally came to a close at the Wyandotte Theater’s Annex section. Its new bill of Blazing Saddles and Chino were the first non X-rated movies to air from there in two months. Resulting police operations around adjacent businesses saw multiple cases of questionable publications being shelved at the Open Book store nearby, though they were within a clerk’s easy view and paper bag wrap covering front pages of the magazines. The operator of the Wyandotte Theater said he was in no control of what was shown at the movie house; responsibility for that fell upon a theater operating company out of Southgate. The good news from all this was that no further scheduled X-rated features were planned to be shown at the Annex for the forseeable future. |

More troubling to the general public were the rapidly increasing counts of school vandalism Downriver, much of which was coincidentally tied to the 1976 showing of the television special “Helter Skelter,” which focused on the Charles Manson family murders of the 1970s. Sibley School in Trenton was vandalized in April to the tune of $6,000 – $7,000, mostly done over a four-hour period of window-breaking. Two area youths were quickly apprehended. “Helter Skelter” graffiti was found tagged in various locations at the school. The same month, Grosse Ile High School suffered $10,000 worth of damage to its structure, with its shop area the hardest hit. Classes there were canceled for two days as cleanup was initiated.

The following week (April 17), alert citizens stopped a possible fire from occurring at Lincoln Junior High School in Wyandotte. A small fire was quickly doused in a classroom. Three wine bottles had also been hurled through windows. Just two days later, a small fire also erupted at Schaefer High School in Southgate. Damage there was not widespread, but the commons area near the gymnasium suffered heavy smoke damage, in addition to an “unknown substance” being found on the floor nearby. At the time, no one knew of any probable suspects. Reaction among various school principals was mixed as to the issue of the television movie being wholly responsible for the uptick in school vandalism.

Construction finally began after over a decade and a half of delays on the Big Barrel storm sewer project in the spring of 1976. Despite all the delays, enough planning had been done to where the project was still estimated to take just two years to complete.

McLouth Steel finds it is not impervious to the 1970s recession

MCLOUTH STEEL

The first signs of stress at McLouth Steel – the newest of the three Downriver landmark steel mills – began surfacing in the 1970s, owing mainly to both the ongoing economic climate of the mid-1970s, as well as the increased proliferation of foreign imports of stainless steel product.

Federal assistance was being offered to those who had been laid off by the steel firm in the preceding few years, as per the Trade Act law of 1974. In just five short years, requests for stainless steel production had plunged from 180,066 tons in 1970, to 85,000 tons by 1975. Although this latest action generally affected only the original Detroit plant (whose payroll shrunk from 1,150 in the early 1960s to 600), it was becoming clear that adjustments at the Trenton and Gibraltar mills might be forthcoming. It was hoped that the federal assistance could aid all three plants.

“Michigan Lefts” and railway bypasses serve to dominate motorist headaches

In May, construction barrels began popping up along Fort Street as the median would be torn up for much of the summer in the Southgate and Wyandotte portions. Workers were installing the first of the now-infamous “Michigan Left” turn-arounds, which back in 1976 were still simply called left-turn lanes. With this project came the questions as to why Fort Street wasn’t widened to four lanes across. There were numerous areas of concern along the route, namely the Fort and Grove Street intersection on the Wyandotte side. Many cars had taken the curve in front of Danny’s Foods too quickly and either skidded off the road or into the ditch, although appropriate blame was also placed on the angle of the curve, not just speed limits.

Meanwhile, a new law had taken effect in late 1975 regarding right-hand turns, specifically on red lights. By the spring of 1976, Wyandotte Police Chief Marion Jezewski cited increasing concern about motorists disregarding oncoming traffic when making these turns, often requiring two lanes to do so. “Turning right on a red light,” the chief admitted, “is not always the best thing to do.”

Blocked rail crossings similar to this one in Woodhaven in the 1970s demanded a information relay system be equipped for both Trenton fire stations in order to help expedite quicker emergency service.

Motorist headaches of the present day are sometimes dominated by the difficulties in navigating around two railroad crossings in the Trenton and Woodhaven areas. These headaches, found on Allen Road, Fort Street and Van Horn Road, were causing delays and inconvenience before the 1970s and current wave of urban sprawl. Much of the arguments in favor of a railroad bypass (over or underground) centered around ambulances’ inability to get from the north end of the cities to the south. In May 1976, a tentative plan was announced which would allow Trenton firefighters a way to get around the daily logjams.

Trenton City Engineer Thomas Seymour introduced an indication system package which would enable the city’s two fire stations to connect directly with the rail crossings via relay. Its purpose would be to send alerts to the fire stations that a train was crossing (and possibly blocking) the affected areas. Fire dispatchers would then be able to send this message to the fire truck en route, where an alternate route through neighborhoods could be quickly taken to save time. The estimated cost to start up this system was pegged at $3,350, including an $8.95 monthly charge by Michigan Bell Telephone for relay service.

“The Bird is the Word” in “secret” pizzeria and in the city of Southgate

The biggest sports name Downriver was the same name capturing attention all over the country: Mark Fidrych, the charismatic Detroit Tiger ace right-hander. He was profiled in the News-Herald at a meet-and-greet for children at a local pizzeria (the news article would not mention the name of it, but safe to say it was likely Little Ceasar’s Pizza Treat on Eureka Road, the former Shakey’s Pizza).

He was as down-to-earth locally as he was in the general public eye. He lived at the Fountain Park South apartments off Trenton and Leroy Streets during the season, where he would be selected as the starting pitcher for the American League All-Stars.

Asked how he liked living in Southgate, he said “it’s alright,” then simply shrugged his shoulders and smiled – definite hallmarks of “The Bird.”

Four Corners plaza in Grosse Ile destroyed in Thanksgiving blaze

Four Corners shopping center on Grosse Ile, circa 1974.

A three-alarm fire resulted in firefighters battling in vain to save the Four Corners Shopping Plaza at the corner of Meridian and Grosse Ile Parkway. After a four hour battle, the building, known for housing the Eat and Greet Nook, was considered a total loss.

The initial cause of the fire was suspected to be faulty wiring, although arson investigation units were still inspecting the property. The building, which had recently been offered on the market for $185,000, had many construction defects which helped spread the blaze quickly. Constructed in the 1930s, it was thought the quality of lumber selected was dried out, there had been no recent fire inspections, numerous false (suspended) ceilings, air tunnels and no modern firewalls which could have contained the blaze.

The most frustrating issue from the firefighters’ perspective, however, was ongoing problems with water pressure, something the Fire Department would say was becoming an “as usual,” all-too common problem. The lines servicing that portion of Grosse Ile were laid in 1935, but a new water line for fire use would cost between $3 and $5 million dollars. In spite of the increasing population of Grosse Ile, that cost was still too high for the Township budget.

Four Corners would never be rebuilt. By the late 1970s, the environmental movement was beginning full-throttle on Grosse Ile. Gone would be the days of building for the sake of building. Although the Open Space Act was still years from passage, the downtick in construction and the new awareness of Grosse Ile’s natural areas would change the course of the township’s evolution.

Tragic story has heartwarming progress for baby Joey Lewis

That Thanksgiving weekend, a horrifying discovery was made inside a Salvation Army dropbox located in front of the K-Mart on Eureka Road. A baby, less than two weeks old, was found inside the bin, abandoned in the freezing weather and covered only by a blanket wrapped in a paper bag. There was no danger of immediate suffocation, but hypothermia was a very real possibility.

| The infant, 4 pounds 11 ounces at birth, was rushed to Wyandotte General Hospital for care. Hospital staff were pleased to report the baby, named Joey Lewis, was eating normally, and his weight was up to 5 pounds 4 ounces. The requests for adoption of Baby Joey were extremely high in number and delighted his caretakers at the hospital, which would ultimately send him to a foster home in the interim once his condition was stabilized. His parents were unknown and neither could be located, although a search for clues was ongoing. | “We hope to keep Joey with us until after the Holidays, because we all want to be Santa Claus.” – JOAN La BADIE Afternoon Nurse, Wyandotte General Hospital |

Eureka Road gets that “sinking” feeling

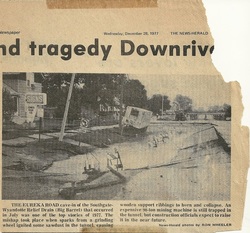

Westbound Eureka after the cave-in, c.1977

In July 1977, an accident underneath Eureka Road caused the westbound section between the railway trestles and 12th Street to collapse and sink, putting this busy stretch of road out of commission for nearly a year.

Work underneath the road had been ongoing as part of the long-running “Big Barrel” sewer project servicing the area. This area project was engineered by Hubbell, Roth & Clark, with United Construction and Mancini Construction the contractors. Temporary tunnel bracing consisted of wood supports, whose sawdust caught fire that day. The fire spread to the wood support braces for the tunnel. Workers from Mancini Construction tried to put out the fire on their own before the Fire Department arrived. They sent down hoses with attachments that twisted, spraying water all throughout the affected area. Due to the fire and/or resulting loss in air pressure in the tunnel, cracks began to quickly form on the Eureka surface and – within minutes – the westbound portion sank along with the surrounding grassy area.

Fortunately, there were no injuries, as there had been enough time to warn motorists and pedestrians about the problem: Eureka had been closed for a couple hours prior to the sinking. Grosse Ile, Riverview and Trenton would lose water service as a result. The Detroit Water Board announced shortly after that water had been re-routed, but to expect lower water pressure than normal. The initial estimated time to repair Eureka Road was six to ten weeks.

Other areas of Eureka were looking better, though. Meijer Thrifty Acres opened their first store Downriver at Eureka & Pardee in Taylor in the summer of 1977.

The first “all in one” store (termed a hypermarket) in the area, it immediately began drawing people in and would foreshadow the current age, where most stores strive to be multi-purpose versus specialty. In a rarity for its time, the Taylor Meijer would be among the many 1970s-built Meijer stores to have a kids-based “Oasis” in the center of the store. This section was hugely popular, but was removed within eight years due to concerns for safety and responsibility.

The Beginning of the End for the Neisner Brothers Chain

The regular Neisner dime stores did not usually sell LP records. The Big “N” chain attempted to, but brought the parent chain down with it.

Despite Downriver hosting three different dime store chains (which seems a small number compared to the numerous dollar stores seen today), Kresge, Neisner and Woolworth & Woolco were all holding their own until 1977, when Neisner would begin faltering.

The chain had decided to experiment with a larger, more traditional department store concept, titled “The Big ‘N'”, which sought to rival stores such as K-Mart. This launch failed, however; which jeopardized its core dime store business. Neisner did its best to ensure its customer base that the firm was healthy, and set out on a renovation that would totally re-dress its Lincoln Park and Wyandotte stores.

New colors (oranges and yellows) were introduced, new store fixtures were installed. To the delight of the dedicated customer base (and on the wishes of its Wyandotte store manager), the creaky, sloping wood floor was retained in its original state to add nostalgia value. It was a nod to history that was years ahead of its time.

This was not enough. Forced to file for bankruptcy, Neisner ended up bought out by the Ames Discount Store chain, and both Downriver stores wound up closed by the end of 1978.

The Arab oil embargo was starting to take a toll not just on automobiles, but on boats. The Columbia and Ste. Claire Bob-Lo boats saw their travel schedules noticeably curtailed, which caused attendance at the park to drop. The park had a particularly bad year from a financial standpoint in 1979, compounded by the fact that steamship excursions were curtailed from Wyandotte due to a lack of quality parking near Bishop Park. So after 30 years of ownership, Todd H. Browning would sell Bob-Lo amusement park and the boats to Cambridge Properties of Kentucky.

Rockwood avoids County Prison construction

Rockwood residents may have had good reason to be alarmed in the spring of 1979, and State Senator James DeSana took notice. In May, he wrote a letter to Michigan Governor William Milliken asking him to stop the proposed construction of a 550-cell prison planned for Rockwood.

The Michigan State Department of Corrections was interested in a 120-acre purchase of land, of which forty acres would be for the prison, while eighty acres would be sold by the D of C. The drain on the tax base would have been two fold: A prison – since it is on exempt state land – does not pay taxes, and there would be an obvious fear for potential businesses to locate or build near a prison site. As a result, residential tax rates would have to rise to make up for the potential loss. In his letter, DeSana mentioned the Upper Peninsula community of Kinross as an alternative home for the prison. Kinross already had a medium-security facility operational, while making it known they would welcome the new project.

Clark Tank Farm explosion forces evacuation of 5,000 area residents

A petroleum storage tank with a 1.2 million gallon capacity went up with two explosions at the Clark Tank Farm on Ecorse west of Telegraph on December 15, 1979, forcing the evacuation of over 5,000 neighborhood residents into the late autumn cold. Flames from the explosion threatened mobile homes in the nearby Robinwood Trailer Park in Taylor, and in fact an undetermined number of them were destroyed. Fortunately, there were no deaths and only one minor injury from the incident.

The first explosion occurred around 3:00 AM and was visible from downtown Detroit. The next explosion, though not as fierce, occurred over seven hours later and hampered firefighter efforts to keep the blaze and hot spots under control.

Though the cause was not officially determined at the scene, it was suggested that the exploded tank had been overfilled with petroleum, with a resulting surface vapor cloud trailing off to the trailer park area. Something as simple as lighting a stove could have taken flames along the invisible vapor cloud, toward the tank.

A sidenote was that looting was a major problem following these incident, as it was reported various youths began breaking into the homes and taking “anything they could find.” A total of nine ended up in police custody, six directly tied to the thieveries.

Downriver tries to show its true grit as the 1980s commence

McLouth Steel during better days in the 1950s.

As the 1980s began, one of Downriver’s most important industries would show signs of trouble.

McLouth Steel, successful for over 40 years in Metro Detroit, a staple in Trenton for 32 years and in Gibraltar for 26 years, began to suffer budget trouble. They had made adjustments in the latter half of the 1970s by reducing payroll and positions from their 1950s heights. Yet as the decade began, payroll remained at approximately 3,775.

More sobering news was provided by the Downriver Community Conference (DCC). It was estimated that Downriver unemployment could be in the 30% range, affecting 30,000 to 35,000 people. Of these, 25,000 were UAW workers, 1,500 at McLouth, 2,000 at Great Lakes Steel, 870 at BASF Wyandotte, plus other yet-to-be-announced layoffs at Dana Corp. and Pennwalt.

It is relatively safe to assume that most of those people – and thousands of others – would witness one of the fiercest weather events to hit the area since the 1950s.

D E R E C H O !

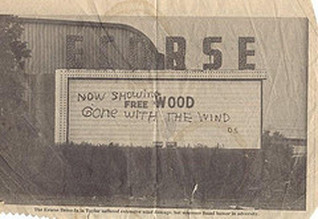

The original screen at the Ecorse Drive-In could not withstand the wind gusts of the Derecho of 1980. |  One of the more memorable – and likely appropriate – graffiti “markings” after the storm. |

DERECHO (GREEN STORM) OF 1980

July 16, 1980 is a weather day that still lives in residents’ minds today. The day started out clear and dry, but by 8:00 AM the perception drastically changed. A weather phenomenon referred to as a Derecho began blowing in from Wisconsin, directly west to east. Within minutes, the sky would turn a dark, pea-green color, followed by extreme gusts on wind (reaching 86 MPH at Detroit Metro Airport, but higher gusts at surrounding stations, some reaching triple-digits).

The storm sped east as quickly as it came, but some of the destruction was extraordinary. Interviewed on our Facebook site in 2014, witnessed concured they had never seen the sky as deep green as they had seen before or since. The Arena section of Thunderbowl Lanes, which had hosted “Bowling For Dollars” as recently as the previous year, was heavily damaged as part of the roof caved in. Railroad boxcars were left scattered like toys on railroad tracks throughout Downriver. Most homes & businesses lost power for up to five days, as high-tension power pylons along I-75 were toppled from Southfield to Schaefer Roads (where the metal towers taper off to standard wooden poles show the proof). The screen literally went down at the venerable Ecorse Drive-In Theater, as the 1940s-era screen became a mangled piece of steel. Part of the facade of the Sears store in Lincoln was blown off.

Fortunately, no serious injuries were reported, and news coverage locally was not even front-page; it was more a summary with a few photos accompanying the article. Within a week, power was restored and any resulting cleanups began.

Cleanup, meanwhile, was the order of the day at McLouth Steel, as they were trying to eliminate the first signs of debt. In September, management went to the workers asking for their first concession: a one year wage freeze. The union force responded with a picket that would last three days, as the union and management inevitably would return to the drawing board.

The passing of a true Downriver legend: E.J. Korvette liquidates

| The drawing board, however, would be removed from the headquarters of E.J. Korvette that fall. Having slumped through flat sales, and two changes of ownership (of the land and business), it was announced that the Southgate store at Fort & Pennsylvania Roads would be shuttering after 17 years. In competition and in step with the competing K-Mart on Eureka Road for many years, the store that astounded everyone at its opening with its sheer size and variety of items… the store which changed the course of discounting and store credit as residents had known it… would be confined to the history books, leaving Chatham Supermarket and Sentry Drug Store as the lone tenants inside Korvette City.The closing was not as bally-hooed as the Downtown Detroit Hudson building would be a couple years later, as it was felt that within time, the Korvette building would undoubtedly house another tenant. News coverage was scant as a result and the closing occured without incident or much fanfare. |  Southgate’s Korvette City in 1978. Southgate’s Korvette City in 1978. |