The Edmund Fitzgerald, circa 1971. (Photo courtesy Wikipedia)

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald was launched from its building yard in River Rouge in 1958, and for the next seventeen years would carry taconite iron ore on a regular route between the Duluth (MIN) area and the Detroit / Toledo areas. The largest vessel of its type on the Great Lakes system thru her entire working life, she would set seasonal hauling records six times. Through the majority of her career, she would be licensed by the Oglebay Norton Corporation during the terms of a 25-year contract.

Her initial safety record was supreme, having been cited for operating eight consecutive years without a lost hour of manpower. She was definitely a source of pride for those who commanded her, namely Captain Peter Pulcer. Quite frequently when going through the Soo Locks, he would emerge with a bullhorn and provide a commentary for tourists at the Locks about the vessel and her specifications. Often he would have music piped out towards the shore whenever traveling the St. Clair or Detroit Rivers for the enjoyment of onlookers, who ranked the ship among the must-watch vessels ever seen in the Detroit River.

Toward the end of her life, she did suffer some small indignities and dings: a run aground in 1969, a vessel collision in 1970, and striking canal locks in 1970, 1973 and 1974. These were not considered unusual; in fact they were to expected for a vessel of her size. None of these minor mishaps threatened the integrity or expected lifespan of the ship: she was estimated to have plenty of lake time left as the autumn of 1975 approached. With vessels of this grade built to to last at least fifty years, it would take its expected life to 2008 if all went well.

Edmund Fitzgerald awaits launch from the River Rouge shipbuilding yards. | (Photo courtesy hazelridgefarm.com) |

DIMENSIONS OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD:

Length: 730 feet Width: 75 feet Draft: 25 feet

Moulded depth (vertical height of ship body): 39 feet

Depth in cargo hold: 33 feet 4 in.

Deadweight capacity: 26,000 long tons

Hull length: 729 feet

The dimensions of the vessel were designed to be the maximum measures allowed to navigate the St. Lawrence Seaway, between Lake Ontario and the Atlantic Ocean. She was named for the then-president of Northwestern Mutual Life.

CONSTRUCTION SPECIFICS OF THE EDMUND FITZGERALD:

Investor: Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee (WI)

Built at the Great Lakes Engineering Works, River Rouge, 1957-58.

First keel plate laid: August 7, 1957

Launch date: June 8, 1958 (10 months, 1 day under construction)

SIDEBAR: It took multiple swings of the champagne bottle to christen her.

RECORDS SET FOR HAULING:

Six in total; heaviest haul was 27,402 long tons (1969)

WORKLOAD:

Average length of voyage: 5 days

Average number of voyages per season: 47

Total number of estimated voyages (as of November 1975): 748

Her final voyage through the untrustworthy waters of the Upper Lakes

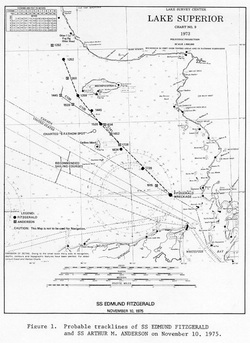

Last voyage route.

Carrying a full cargo of ore pellets with Captain Ernest M. McSorley in command, she embarked on her final voyage from Superior, Wisconsin to Zug Island near its home port of River Rouge. She set sail from Wisconsin on November 9, 1975 with a full load. Joining the Fitzgerald shortly after setting sail was the SS Arthur M. Anderson.

Weather reports predicted a pre-winter storm of average intensity would strike the south part of Lake Superior a day into their route. The SS Wilfred Sykes, traveling two hours behind, received a different weather report saying that the approaching storm was major and would affect the entire lake. The Sykes elected to take a safer route out of the eye of the upcoming storm (to the north near the shoreline). The Edmund Fitzgerald and Anderson ships did not follow suit, instead taking their normal down-lake route. By 7:00 PM, the weather forecast was upped to Gale warnings for Lake Superior. By the time word reached these two ships, they were not in a position to evade the effects of the storm; the only thing that could be done was for the crews to try and ride out the storm.

When they finally met the elements, this severe winter storm had near hurricane-force winds and waves up to 35 feet high. Shortly after 7:10 p.m. Fitzgerald suddenly sank in Canadian waters 530 feet deep, approximately 17 miles (15 nautical miles) from the entrance to Whitefish Bay near the twin cities of Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan & Ontario. Although Fitzgerald had reported being in difficulty earlier, no distress signals were sent before she sank. Her crew of 29 all perished, and no bodies were recovered.

| “I have a ‘bad list,’ I have lost both radars, and am taking heavy seas over the deck in one of the worst seas I have ever been in.” – CAPTAIN ERNEST M. McSORLEY Edmund Fitzgerald “We are holding our own.” – CAPTAIN McSORLEY The last radio communication heard from the Fitzgerald |

Discovery of the downed vessel was rather quick

A U.S. Navy Lockheed P-3 Orion aircraft, piloted by Lt. George Conner and equipped to detect magnetic anomalies usually associated with submarines, found the wreck on November 14, 1975. The Fitzgerald lay about 17 miles (15 nmi; 27 km) from the entrance of Whitefish Bay, in Canadian waters close to the international boundary at a depth of 530 feet. A further November 14–16 survey by the United States Coast Guard using specialized sonar equipment revealed two large objects lying close together on the lake floor. The U.S. Navy also contracted Seaward, Inc., to conduct a second survey between November 22–25.

Finding of the actual Cause of Fitzgerald’s sinking would take longer

Even today, the actual root cause of the ship’s sinking can be traced to several theories:

* Weather conditions were obviously the prime culprit, with Gale Warnings growing to Storm Warnings, affecting mostly the southeast end of Lake Superior, where the Fitzgerald was.

* The rough seas, which were already spouting huge waves, could have also spouted a Rogue Wave, also called “Three Sisters”, where three waves smack a surface before any water can drain off that surface, thereby increasing the chances of flooding and submerging of a vessel.

* According to a survey released in July 1977, hatches on board may not have been closed properly. Underwater exploration showed the majority of the hatch clamps were in pristine condition, with a few of them damaged. The United States Coast Guard, which provided the report, theorized these damaged clamps were the ones fastened on the last voyage.

* The ship had run aground on a reef during the worst of the storm (likely the reef in question was Six Fathom Shoal near Caribou Island). The shoal in fact may have been mis-mapped as it appeared to jut out a mile further than official maps showed, and the Fitzgerald may have hit it in this one-mile stretch.

* Structural failure due to age or general condition has been cited. Views of the wreckage – which is in two pieces – show that the ship fractured upon hitting the lake floor, not as it sank into the Lake.

* Topside damage occurring the previous day (November 10th) involving missing vents and a fence. Water may have poured through the open vents during the storm on its way toward the cargo holds, which was undetected by Captain McSorley.

Numerous other potential factors included lack of instrumentation, watertight bulkheads, and even complacency on the Captain’s part.

The Edmund Fitzgerald as it would appear underwater. The lack of a substantial debris field between sections would help suggest the vessel broke apart upon landing on the lake floor. CLASSIC LYRICS: The Edmund Fitzgerald as it would appear underwater. The lack of a substantial debris field between sections would help suggest the vessel broke apart upon landing on the lake floor. CLASSIC LYRICS: “At 7 p.m. a main hatchway caved in, he said, ‘Fellas, it’s been good to know ya.’ ” REVISED LYRICS: “At 7 p.m., it grew dark, it was then he said, ‘Fellas, it’s been good to know ya.’ “ | ABOVE: Front page of the Kalamazoo Gazette, dated November 12, 1975. Lightfoot’s song cements its legacy Canadian songwriter Gordon Lightfoot took it upon himself to write and compose his now famous ode to the ship and its memory once he noticed a Newsweek article on the sinking misspelled the vessel as Edmond Fitzgerald. Declaring that typo a personal mis-service to the 29 crewhands who perished, he set out to compose the song for one of his upcoming albums.In recent years Lightfoot has (for some of his live performances) changed one of the lyrics two-thirds of the way through the song, and stated in an interview with the Toronto Sun that many surviving family members are grateful for the change: “The mother and the daughter of two of the deck guys who would have been in charge of that have always cringed every time they’ve heard the line. And (now) they will be very pleased… They know about it and they’re very happy about it.” derecho islands geography |