The United Auto Workers gain traction at the Rouge Factory Complex, 1937

Henry Ford, undated. Henry Ford, undated. | In spite of Henry Ford’s groundbreaking changes to the workday procedures; the introduction of the assembly line in 1913, and the $5.00 per day workday in 1914 (which equals $120 per day today), relations with workers were not always positive. The fact was, he despised unions of any type, writing his complaints in detail in his book, My Life And Work. His thought was that increased productivity would be good for the economy, and he saw unions as groups that sought to cut productivity in order to foster more employment. |

Mr. Ford saw potential union leaders as those who would foster a false sense of security in the socio-economic climate, which he felt could lower productivity on his assembly line. He sought good, loyal managers who would be quick to fend off any rise in union activity in any of his factories and shops. Notable among these he brought in was former Navy boxer, Harry Bennett, as head of the Service Department. In addition to siding with Mr. Ford in the 1932 Ford Hunger March, he would end up playing a major role at the Battle Of The Overpass.

The Scene is set for the birth of a new Union

Harry Bennett, Henry Ford’s right-hand man for controlling the interest of unions, c.1937. (Courtesy reuther.edu)

Despite the Great Depression having taken the steam out of the economy in 1929 and through the 1930s, there had been a slight uptick in the wage of the average Ford worker, though very slight: from $5.00 in 1914 to $6.00 in 1937 (the 1937 rate equaling to $96.00 per day in today’s dollars), which most seasoned workers found unfavorable. The United Auto Workers Union, formed two years earlier and making its name known by mediating the Flint Sit-Down Strike of December, 1936, engineered a flier to be distributed among its membership, titled Unionism, Not Fordism.

This leaflet was to be presented en masse to workers of the Rouge complex, at the pedestrian overpass over Miller Road, near present-day Gate 4. The developing union and its workers would present its demands of an unprecedented $8.00 workday ($131 today) before a potential audience of 9,000 workers changing shifts at the plant on May 26, 1937.

It began with a request for a photograph… and then everything broke loose

James E. Kilpatrick, photographer for the Detroit News, was on-site shortly before the shift change and asked UAW organizers Richard Frankensteen and Walter Reuther to pose for a photo on the overpass, with the large Ford Motor Company sign in the background. At the same time, as many as 40 men (the exact number is disputed) from the Service Department, headed by Bennett and functioning as an internal security force, jumped them from behind.

The exact moment of the confrontation’s genesis. Second from right is Walter Reuther, who would become the first head of the United Auto Workers Union. (National Archives) |  Battle Of The Overpass in full-blown mode, May 26, 1937. (National Archives) |

Seven times they raised me off the concrete and slammed me down on it. They pinned my arms . . . and I was punched and kicked and dragged by my feet to the stairway, thrown down the first flight of steps, picked up, slammed down on the platform and kicked down the second flight. On the ground they beat and kicked me some more. . .

– WALTER REUTHER, describing the battle

More action taking place between the union and the “Security Force.” (Courtesy reuther.edu) |  Richard Frankensteen (at left) with Walter Reuther after the battle concluded. (Courtesy reformation.org) |  The shirt, tie and vest worn by Richard Frankensteen during the Battle Of The Overpass, modern day. (Courtesy michi101.blogspot.com) |

The Aftermath: Front page news, bad news for Ford, good news for the UAW

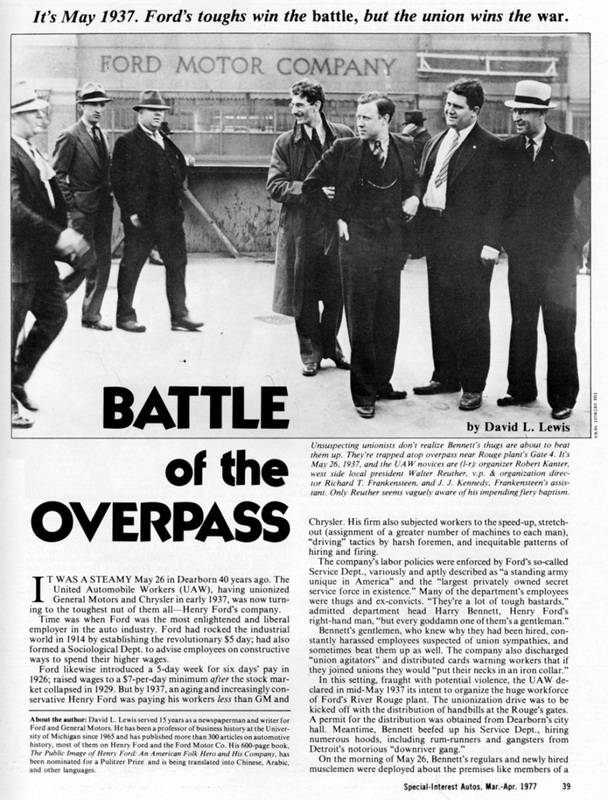

| There were no casualties as a result of the event, although Union organizer Richard Merriweather suffered a broken back in the melee.The Service Department detail then started after Kilpatrick and his photographic plates, intending on destroying them to wipe away evidence of a scuffle. However, Kilpatrick was able to decoy the group by surrendering useless plates without images; the images he kept and developed were hidden in his car. Once developed, printed and published, the incident would become known around the world. Bennett, however, would continue undeterred in his defense of the battle against the Union organizers, in spite of there being many ear- and eyewitnesses: The affair was deliberately provoked by union officials. . . . They simply wanted to trump up a charge of Ford brutality. … I know definitely no Ford service man or plant police were involved in any way in the fight. – HARRY BENNETT |  Reflections of the battle, 40 years later, from a 1977 publication. Reflections of the battle, 40 years later, from a 1977 publication. |

The United Auto Workers gained tremendous momentum through this incident, further cementing the idea of unionized workers in the automotive industry.

In an ironic sidenote, Bennett would be Mr. Ford’s first choice to succeed him as President of Ford Motor Company upon Edsel Ford’s passing in 1943, a distinction which ended up going to Henry Ford II by 1945. Said the elder Ford regarding Bennett some time later: “Well, now Harry is back on the streets where he started.”